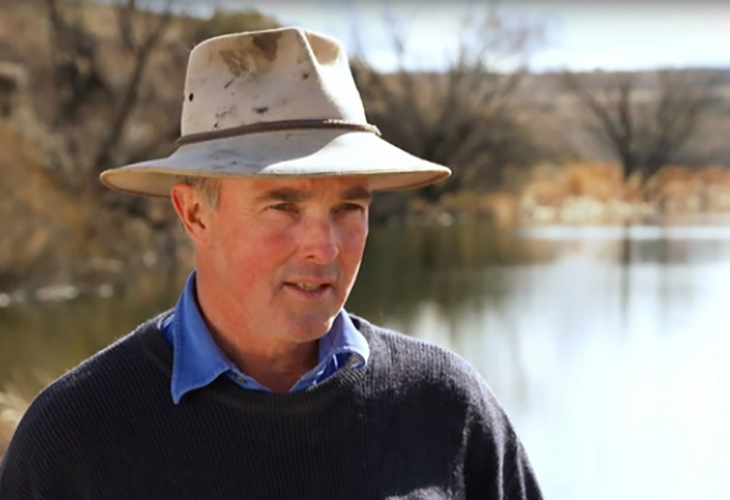

Charlie and Anne Maslin, 'Gunningrah', Monaro

Charlie and Anne Maslin from the Monaro of NSW use regenerative agriculture to maintain ground cover, flowing streams and feed on offer.

Charlie Maslin talks about how his 'drought proofing' strategies for his regenerative farm, aimed at keeping his groundcover, can capture rain when it comes - heavy or not. In this exclusive series of interviews for Soils for Life, prominent Australians lend their perspective on the fundamental role that soils play in our urban and rural landscape. You’ll hear from prominent influencers, a chef, an innovator, a gardening guru and several of our most advanced farmers.

With so much of eastern Australia still in drought, how do woolgrowers Charlie and Anne Maslin from the Monaro of NSW still have full ground cover, flowing streams and no need to back up the feed truck?

Charlie and Anne Maslin own ‘Gunningrah’, 20 km north-west of Bombala in the NSW Southern Tablelands. On the 4200-hectare property, which comprises predominantly native grasslands, they run medium wool Merinos and cattle.

Gunningrah has been managed by the Maslin family for more than 100 years. Charlie and Anne took on its management in 1987, which was when they observed significant annual variations in its rainfall – and profit. While annual rainfall averages 550mm, it has varied from 250mm to 1000mm over the past century.

Examination later revealed the significant impact of low rainfall on the cost of production: wool production costs could double when existing pastures were insufficient, due to supplementary feeding or agistment costs. Furthermore, a mid-1990s third-party analysis of their pastures revealed alarmingly lower levels of ground cover (more than 30% bare ground) than the Maslins had perceived.

After managing the property for almost a decade, Charlie and Anne realised that Gunningrah was gradually facing ecological deterioration and profitability was becoming increasingly variable.

Crucially, it became clear to them that effective management of inconsistent rainfall was a key factor in maintaining profitability. While they couldn’t change how much rain falls, they could change how to manage the rain they are lucky enough to receive.

So the Maslins changed their mindset to focus on the health of the land, which has resulted in the Maslins managing poorer rainfall years more effectively and not over-using pastures in abundant years.

Maximising the retention of available rainfall and striving for much improved ground cover has delivered more consistent profits on reduced inputs. In addition, erosion is being controlled, weed invasion has reduced, stock are healthier and management is more flexible.

Charlie sums up their new approach: “Rather than us dictating to the land what stock it has to carry, we try to look after the land, evaluate what it has to offer and then attempt to stock it accordingly.”

MAINTAINING GROUND COVER

Charlie and Anne’s focus has been to lift ground cover and improve the water cycle of their country so that when it gets rain there’s very little run off. Over the past 20 years, they have increased ground cover levels from the mid-60% level up to about 90%.

“Especially in dry times like we have experienced in the past 18 months, we need to be holding as much moisture in the soil as we can for the plants to grow and the animals to eat, and then for us to make a profit,” Charlie said.

“By building up the ground cover over the years, we’ve increased the infiltration of water into the soil and improved the organic matter which help limit moisture evaporation – and once we've started to get that happening we've been able to reduce the runoff from the property quite considerably.

“Growing periods have extended as the water is now held in the pasture for longer, rather than running off straight into the dams.

“By greater water infiltration and retention in pastures, we are making much more of the rainfall that we do receive.”

INTRODUCTION OF LEAKY WEIRS

A photo taken of a ‘leaky weir’ on Gunningrah’. The creek corridors where they have put the weirs usually remain pretty lush, no matter what the season.

The main source of water inflow to the property is the Cambalong Creek, which flows though the property for 16km. Three smaller streams also flow into the farm.

The Maslins found that using the techniques of Natural Sequence Farming – constructing ‘leaky weirs’ across their creeks and gullies – the health of their watercourses and adjacent pasture could be significantly restored. Since the mid-1990s, the Maslins have constructed a number of small leaky weirs across Gunningrah’s streambeds and gullies.

“Leaky weirs serve to slow down the rate of runoff through water courses, especially after rain, converting intermittent torrents into more constant gently flowing streams,” Anne explained.

“The weirs slow the flow of water, creating a chain of ponds similar to what existed before white man. Sediment is deposited, gradually rebuilding the eroded creek bed. The weirs allow time for water to percolate into the soil layers and rehydrate the landscape and water table. The rich sediment is retained in the landscape, rather than flowing straight out to sea.

“We now have a healthier creek system, it acts like a sponge, absorbing rain as it falls, and conserving water for the inevitable dry years.”

ROTATIONAL GRAZING OF LARGER MOBS

A photo taken in February 2019 of the Maslins rotationally graze their sheep in large mobs in a 10-15 paddock cycle – which enables pasture to regenerate, better stock health and more efficient management with lower labour costs.

The Maslins believed that grazing could be profitable and sustainable by shifting the focus from maintaining a set level of stocking to varying the stocking level according to the productive potential of the pasture.

They implemented time-controlled rotational grazing, matching stock numbers to land carrying capacity. Stock are grazed at a high density for short periods of time (about five to seven days) in paddocks (of about 100 hectares each) as per the determined carrying capacity, followed by sufficient recovery periods to allow pasture to regenerate.

“We put sheep into mobs of 1,500 to about 2,000 and the cattle into mobs of about 200 to 300 cows, and we move those around so that each group will have 10 to 15 paddocks in the cycle,” Charlie said.

“The paddocks that are not being grazed have a chance to grow, to recover, and there’s a chance for seeds that are there to germinate and grow – and that has been one of the largest things that has lifted our profitability. Grass diversity, particularly native species, increased quite quickly after the establishment of rotational grazing.”

Charlie also says stock rotation provides an early warning system of land recovery. “If the pasture in the first paddocks is not fully recovered after a rotation cycle has been completed, an informed decision can be made on stocking rates. With set stocking, it was only when stock condition started to deteriorate that pasture problems were identified.”

Other benefits the Maslins have experienced include improvements in stock health. “The worm burden has been substantially reduced by the continual stock movement and the resting of pastures over the summer months. Animals are now only drenched once or twice annually, as opposed to four times a year previously. Twin lambing pregnancies are 20% higher than two decades ago and stock classing is more consistent.”

LOWER COST OF PRODUCTION

In terms of inputs, Charlie says larger mobs enable more efficient management. Movement, drenching and stock checks now require less human input. Stock are becoming easier to handle with more even temperaments due to greater human exposure.

“A lot of people think that because you're moving stock quite regularly with rotational grazing that your labour input goes up – but that’s not the case,” Charlie said. “We’ve kept detailed records of how we’ve allocated time, and since we’ve been doing rotational grazing, our time doing stock work is down about 40%. It used to take just more than 300 people days a year to do all the stock work, now we do it in about 180/200 days.

“It’s because, for instance, when we join the sheep there are two mobs to join whereas before we had probably 30, when you crutch them we had 30 mobs to bring in whereas now we have two, and when you're checking for flies you can check two mobs in the space of a couple of hours whereas before it would take you two or three days.

“Labour is the most significant cost you have in running a property and we're able to run our stock with less labour. Since we’ve changed our grazing management, we’ve had a lot more time to do other developments, such as plant trees, new fencing work and put reticulation schemes in.”

CHANGES TO INFRASTRUCTURE

An extensive capital outlay was needed in implementing a new water reticulation scheme as the water cycle slowed down and dams could not be relied upon. All troughs are gravity-fed, so no fuel is required for pumping. Charlie points out: “While costly, establishing the troughing system is ultimately much more water efficient than dams. There is now less evaporation, wastage, land damage, and the stock have access to cleaner water.”

Additional expenditure was required for fencing and other necessary structural changes. Whilst these new capital costs were significant, they did not restrict implementation of the new methods. “We implemented the grazing first, and made the necessary structural changes once we saw what was needed.”

A HEALING PROCESS

The land has been a major winner as a result of the changed water management and grazing practices on Gunningrah, with positive outcomes in relation to water use efficiency, soil organic content, vegetation cover, and minimising erosion by wind and runoff.

Grazing changes and increased ground cover have assisted in reducing weed problems. Water courses are now only exposed to livestock activity for short periods of time, which protects banks from damage and further allows sediment build up and vegetation a chance to germinate. The Maslins have also undertaken broad planting of tree species found to thrive in the region.

Improvements to soil and water quality strongly support increased biodiversity. In addition to increases in pasture diversity (which improves the health of livestock), there is increased birdlife, and even platypuses are now regularly observed in the Cambalong Creek.

Perhaps most importantly – aside from the very welcome increased profitability, which is a combination of better utilisation of rainfall and good commodity prices – the Maslins have found that the changes they have adopted have freed up more time for them to do other activities they enjoy; the extra family time in particular has been greatly appreciated.

More information: Charlie Maslin: gunningrah@gmail.com. For more information, view a case study at www.soilsforlife.org.au/case-studies/gunningrah