Pole position: update on best-practice barber’s pole worm control in sheep

The level of worm infection appears to be increasing in Australian sheep flocks. This problem is compounded by common sheep worms developing resistance to drenches. Fortunately, dramatic improvements in productivity and welfare of sheep can be rapidly gained using genetic selection, monitoring, vaccination, drench testing, pasture rotation, feed supplementation and careful flock management.

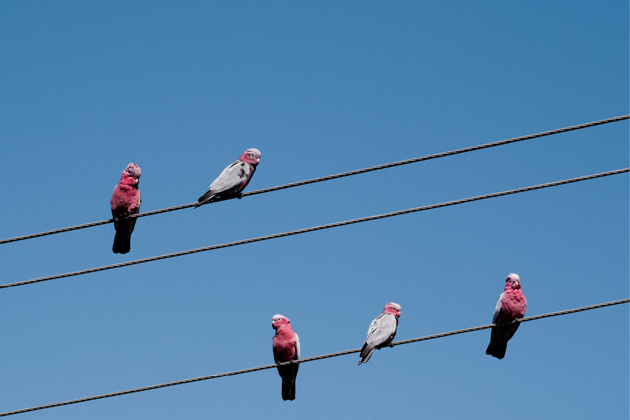

Main image: Adult Haemonchus contortus (barber’s pole worm). Vethamzah, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Authors: Matt Playford, Dawbuts; Megan Rogers, Megan Rogers Consulting; Emily King, AWI National Extension Manager

Reports from sheep producers across Australia are telling a familiar story: the sheep have worms. Especially barber’s pole worms. Growers are losing wool production, lambs and ewes. Growth rates are slow. Worms are harder to control now than ever before.

NSW data from the Dawbuts Kamiya Laboratory shows that from 2020–2025, mob average worm egg counts (WEC) for barber’s pole worm peaked in autumn at 770 eggs per gram (epg) and remained above 300 epg over winter. This is considerably higher than the levels monitored during the drier years of 2015–2019 (600 epg peak and 200 epg across the winter months). Other states show similar trends.

It can be very distressing to deal with a problem that seemingly has no practical solution. In this article, we look at some new research, as well as tried and tested ways to control worms that you can apply to your flock.

Where are the worms?

It is estimated that on an average sheep property, only 5% of the worms are actually in the sheep. The other 95% are completing their life cycle in the pasture.

Knowing the status of worms on your pastures is key to understanding the risk to your sheep.

Worms start off as eggs dropped in the dung and develop to third stage larvae, the infective stage (also known as L3), which live in the grass. This may take only 4–5 days under warm, wet conditions.

Barber’s pole worm eggs are sensitive to cold (below 10°C) and dry (less than 2 days’ rain or equivalent), so die rapidly in cold or dry weather. However, once hatched, the larvae are hardy and survive for up to 12 months. Other common worm eggs (brown stomach worm, black scour worm) will survive up to 30 days in faecal pellets, emerging as larvae when conditions (moisture and warmth) allow.

Studies have shown that most of the worm larvae are found in the bottom 5 cm of the grass sward, with very few climbing above 10 cm. This puts them in prime position to infect sheep, which tend to graze low on the pasture. Counts of larvae on Australian pastures reveal that contamination of pasture can reach 20,000 larvae per kilogram of dry matter (20,000 L3/kg DM). Each time a sheep eats a mouthful of grass on infected pasture, they take in dozens of larvae, which then continue to develop in their guts.

Because a sheep will typically eat about a kilogram of dry matter of pasture per day, this results in a very high dose of infection. Even half this dose (10,000 larvae) is enough to cause severe, life-threatening anaemia.

Impacts of barber’s pole worm

Once barber’s pole worms reach the fourth stomach (abomasum) they start sucking blood. An adult female can suck 0.05 mL of blood per day, meaning that it only takes 2,000 adult worms to suck 100 mL of blood from the sheep per day. Sheep develop anaemia, which can be seen in the pale colour of their lower eyelids. Use the FAMACHA test to check your own sheep. Other signs are bottle jaw, a soft swelling below the mandible and inability to exercise, meaning they will fall over when mustered.

Research in Australia shows that with higher WEC, blood oxygen levels drop to very risky levels. In Armidale, NSW, ewes with WEC of 1,200 epg were shown to be 3.5 times more likely to die than those with WEC of 600 epg.

New Zealand research shows that there is also an impact of weight gain of lambs when larvae are ingested. This is partially dose-dependent, but once a certain threshold is reached (estimated at 1,000 larvae), lambs fail to thrive.

Feed and condition score impact sheep’s resilience to worm infection

Analysis of records from Dawbuts Kamiya Laboratory from 2015–2025 show a negative correlation between condition score (CS) and WEC. Mobs of sheep in CS 1 and 2 had higher WECs in each month of the year, compared to sheep in CS 2.5 or more. This phenomenon is related to nutritional reserves available to sheep to fight off worm infection.

A related situation occurs with feeding levels. Studies on lambs infected with barber’s pole worms in Mexico showed that lambs fed at a higher level were able to maintain relatively low WECs and had less anaemia than lambs on poor nutrition.

The message is that resilience (the sheep’s ability to have good production in the presence of worms) can be boosted by higher CS and better nutrition. Note that this doesn’t make a mob bulletproof and, particularly with barber’s pole worms, large infections leading to anaemia and death can occur even in heavy sheep.

Condition score targets of >2.5 CS are also critical for optimising productivity in sheep enterprises, driving important outputs such as wool growth and reproduction.

Monitoring is key to managing worms more successfully

Taking faecal (dung) samples for WECs remains the simplest and most practical way to monitor worm burdens in sheep. Many methods, including new technologies, are now available and all can be used with confidence, as long as the operator is accredited under the ParaBoss WEC QA system. Look for the logo below at your provider or use this handy search to find a ParaBoss WEC QA certified provider to work with.

Once you know the type of worms present and the WEC, either as a mob average or a range of figures from individual sheep samples, you can decide on management options.

Counter-measures for optimum outcomes

Drenching sheep has long been a mainstay of worm control, but due to worms developing resistance to all drenches, it is no longer reliable. Producers must conduct their own drench test to check the status of resistance for each of the worms present on their property. Only use drenches that have greater than 95% efficacy against each of the worms present.

Check that the drench has worked, by doing a follow-up WEC 14 days after treatment.

Make sure you only drench if it is necessary, as over-drenching leads to worse resistance. Evaluating CS, FAMACHA, average daily gain (ADG), and vigour can help qualify the results of a WEC test.

Adhere to best practice drenching protocols

Adhering to best practice drenching protocols is paramount in the quest to elicit good worm control and minimise the negative impacts of parasites on the flock. Best practice drenching protocols include several simple steps, including:

- Test – don’t guess: complete a WEC before drenching to find out what the worm burden is and know which worms you are dealing with.

- Select a product that is fit for the job – get advice from a trusted, and experienced advisor.

- Use combination products in preference to single active products.

- Read the product label – pay particular attention to withholding periods, export slaughter intervals, and other important information such as precautions (conditions for administering the drench).

- Weigh animals and drench to the heaviest in the mob. Draft into weight ranges if a high variance exists.

- Ensure equipment is in proper working order – calibrate the drench gun.

- Thoroughly shake the drench drum every time before use.

- Follow up with a WEC 10–14 days after drenching to be sure your efforts and the product you used have been effective.

Drench decision guides are available on the WormBoss website and can be used to assist with determining if drenching is warranted.

Grazing management is very beneficial

Grazing management, including pasture spelling, moving sheep prior to egg development to L3, rotating with cattle, and making hay or silage, are all great ways to reduce the contamination of larvae in a pasture. ‘Crash grazing’ or high stocking rate grazing with worm-free sheep for short periods can also rid the paddock of worm larvae. The re-grown pasture is then safe for young stock. Strategies for preparing low-risk worm paddocks for different regions can be found at WormBoss.

Making a ‘traffic light’ farm map with red, yellow and green ‘signals’ on each paddock according to their estimated contamination levels helps with decisions about paddock rotation.

Other methods of controlling worms

Fungus, such as Duddingtonia flagrans which is found in the commercial product BioWorma®, can be used in feed to kill worm larvae in dung. This fungus is effective but only when it is fed every day, so often has limited application in extensive grazing situations. Where this fungus can often be used well is in high value, set stocked sheep, for example, in the ram paddock. Growers will need to decide the benefit–cost of using this approach for their situation and should take into account drench resistance issues individual to their property.

The use of Barbervax is very helpful in flocks with heavy barber’s pole worm issues. Barbervax is a vaccine that helps the sheep mount an immune response to the barber’s pole worms and can greatly reduce the numbers. Several boosters are required, and it is recommended you seek expert advice if you’re considering using this tool. It does not eliminate the need for drenches, but it can help reduce the number of drenches needed in the peak season.

Genetics is one of the best long-term ways to control worms in sheep. Selecting animals with a lower Australian Sheep Breeding Value (ASBV) for WEC will produce progeny that are more resistant to worms. These genetic benefits are cumulative and permanent.

Work in Armidale, NSW by CSIRO and University of New England researchers show dramatic reductions in worm egg output and improvement in lamb welfare when either vaccine or genetic selection is used, but the benefits are compounded when both are applied.

More information

- AWI webinar (November 2025) – Pole position: staying ahead of worms this summer

- AWI Parasite management

- WormBoss

- ParaBoss webinars

- WormBoss Worm control programs for sheep

- ParaBoss WEC QA accredited advisors

- WormBoss Grazing management – sheep

- WormBoss Summer pasture management – preparing low risk worm paddocks in summer rainfall areas

- Sheep Genetics Health ASBV fact sheet

- Making More From Sheep Tool 11.8 Management of worms

- Making More From Sheep Tool 11.9 Management of drench resistance