A whole new world for the Merino

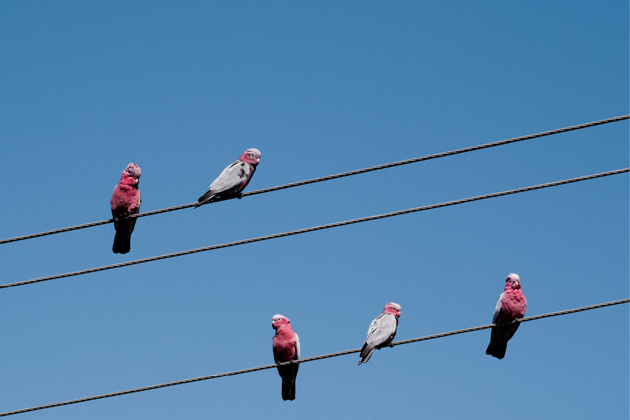

At Yarrawonga, near Cunningar in the South West Slopes of New South Wales, the Phillips family is showing how the modern Merino continues to thrive as part of a successful, balanced enterprise.

Across seven properties, Steve and Liz Phillips and their son Sam, the fifth generation on the land, manage 20,000 Merino ewes joined to Merino sires, another 10,000 joined to terminals, and 1,000 Angus cows.

About 2,500 acres are used for grazing crops, with Merinos remaining the main focus of the enterprise.

The Phillips family also sell around 600 rams annually to local and interstate clients, from southern and central NSW to Victoria and Tasmania.

Sam, the fourth generation on the farm, represents a forward-looking attitude that’s shaping a new kind of Merino enterprise: one that’s every bit as profitable for meat as it is for wool.

“People who used to be 40 percent livestock and 60 percent cropping are now 70 percent sheep,” said Steve.

“And most of those are Merinos.”

The Modern Dual-Purpose Package

Once considered the domain of fine-wool production alone, today’s Merino is as versatile as it is valuable.

The Phillips family run both Merinos and crossbreds, yet it’s the Merinos that consistently deliver the best return.

“Our Merinos make more money than our crossbreds,” Steve said.

“Mainly because of the extra income from the wool.”

It’s an increasingly powerful equation: a Merino lamb worth around $300, its fleece adding another $80, and the ewe behind it producing a valuable fleece of her own.

“It’s an extremely good package,” said Steve.

“The Merino is the whole package – meat and wool.”

In recent seasons, Merino wether lambs have been returning over $400 per head when both fleece and carcase values are combined.

“The versatility of the wether is very attractive – the profit margins are so much bigger,” said Steve.

“Then you have the versatility of the Merino ewe – the cull ewes can be joined to terminals for cash flow, and you still have the wool from them. She’s the cornerstone of the sheep industry.”

Genetics and Growth

Yarrawonga has evolved with the modern Merino’s transformation.

Steve said they transitioned to what they call the he modern Merino about 15 years ago.

“They’re plainer-bodied, more fertile, longer-stapled and finer. You don’t have to go broad to have a multipurpose Merino,” he said.

The flock now averages around 18-micron, with strong early growth rates and high fertility. Steve said ASBV data has become essential for ram clients.

“Most young people want to see them now. It’s becoming more predictable – you can pick traits and growth rates,” said Sam.

“We DNA both ewes and rams. It’s worth it.

“We found the top one and five percentiles are the ones people are focussing on.”

Their feedlot operation at Gundagai puts the Merino’s modern value to the test.

Each year, 3,500 lambs cycle through on grain for around 60 days.

“All the lambs that went into the feedlot had all their feeding costs paid for from their wool income,” said Sam.

“The Merino wool covers the feed. That’s the difference.”

He said growth and performance are now on par with crossbreds.

“People just have to feed them like a crossbred lamb. If you do, their growth rates are just as good.”

The Ewe at the Centre

The Phillips’ see the Merino ewe as the foundation of everything.

“You go to most enterprises that have good Merino sheep, it’s their best money maker,” Steve said.

“It’s all about the money the Merino ewe produces – and it can come from either side, wool or meat.”

With strong wool values and solid meat prices, he sees potential for the national Merino flock to grow again.

“If both the meat and wool markets retain their strength, I think there’s every chance Merino numbers will increase,” he said.

“It’s a complete package now – meat and wool. It must be sold that way.”

A future built on quality

As for what’s next, Steve believes it’s all about recognising how far the breed has come.

“The world is full of grain – they can grow grain anywhere in the world,” he said.

“But wool, they can’t grow everywhere, and not quality wool like ours in Australia.

“The work that has gone into the Merino flock over the last 50 years is incredible.

“Everyone’s micron has probably dropped two or three, and we’re producing better wool than anyone else in the world.”

It’s a sentiment echoed across their enterprise – a quiet confidence that the Merino has re-emerged as the backbone of profitable, adaptable sheep production in Australia.

“It’s a whole new market for Merinos now,” he said.

“The wether lamb market hasn’t been there in the past like it is now. But I don’t think we’ve had the wether lambs we have now. Better genetics, better feeding, better management – they’re simply a more productive sheep.

“It’s a whole new world for the Merino. You have to look forward, not backwards.”

For the Phillips family, that forward focus is clear — continuing to breed, feed and manage a sheep that delivers consistent returns and flexibility for the modern farm.

The Merino has proven itself again, not just as a wool sheep, but as a dependable, profitable all-rounder for Australian conditions.