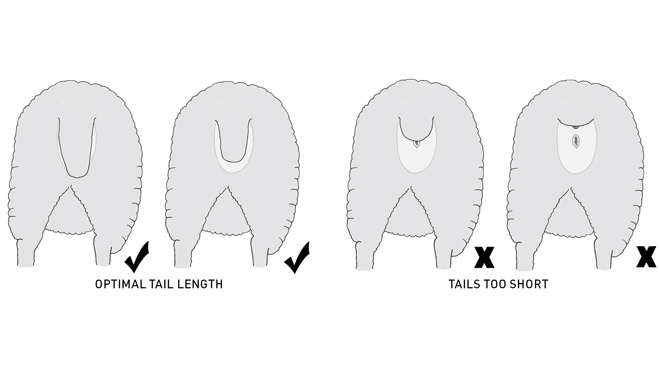

Tail length matters!

Tail docking is a standard practice in the sheep industry and is important in helping reduce susceptibility to flystrike, but care must be taken to do it correctly.

Sheep with optimal length tails have lower rates of flystrike, prolapse, perineal cancer and arthritis than sheep with medium or short tails.

Tail docking is a standard practice in the sheep industry and is important in helping reduce susceptibility to flystrike, but care must be taken to do it correctly.

Australian sheep producers are often docking tails too short, according to results of a 2021 survey conducted for AWI and Meat & Livestock Australia.

Bridget Peachey, AWI General Manager, Research, Sheep Health and Welfare, said from all producers surveyed the average tail length for ewes was 2.5 palpable joints from the body and for wethers was slightly shorter at 2.4 joints.

“This is not long enough for optimum sheep health and welfare,” Bridget said.

“There is ample evidence that an optimal tail, that is a tail docked at the third or fourth palpable joint, is better than a short tail.”

Sheep with optimal length tails have lower rates of flystrike, prolapse, perineal cancer and arthritis than sheep with short tails.

Sheep veterinarian Dr Joan Lloyd, whose research confirmed the link between short tails and arthritis, said it was disappointing that short tails were still prevalent in the sheep industry.

“Most arthritis in Australian sheep is caused by bacterial infection. The bacteria enter the sheep’s bloodstream via a wound. It can occur through any skin tear, but short tail docking is especially problematic,” Dr Lloyd said.

“When tails are docked too short, more muscle and tissue is involved. The wound takes longer to heal, which means it has more chance of becoming infected. One of the consequences of infection is arthritis/polyarthritis, which occurs when bacteria spread through the blood to the joints.”

Dr Lloyd conducted extensive post-mortem examination of sheep and found rates of arthritis/polyarthritis are likely to be more common in lambs in southern Australia than suggested by abattoir surveillance data, with an average of 2% of carcases affected within affected lines.

“Arthritis is a serious sheep health and welfare concern from short tail docking, but it is not the only issue with the practice,” she said.

“The damage to muscle and other tissues means sheep with short tails are unable to lift their tails to defecate. In ewes, this also applies to urinating. This means short tails tend to lead to higher dag formation and, in ewes, more urine staining. These things in turn lead to higher rates of breech flystrike. It seems counter-intuitive that a short tail would cause more flystrike but the evidence has long supported this fact.

“Research conducted in the 1930s and 40s established this link. The research was conducted on unmulesed sheep and is as relevant today as it was then.”

The research, conducted prior to the availability of modern flystrike prevention chemicals, reported flystrike rates in sheep with short tails as being more than double that in sheep with long tails. In long tailed sheep 13 sheep per 100 were struck, in medium tailed sheep the rate was 27 per 100 and in short-tailed sheep it was 38 strikes per 100 sheep.

“The best length to dock a sheep’s tail is in the vertebral space after the third or fourth palpable joint,” Dr Lloyd said. “The remaining tail should cover the vulva in a ewe and be the equivalent length in a ram or wether. Another good landmark is the bare area on the underside of the tail. The bare area on the underside of the tail should never be cut through. Leaving this bare area intact means the animal will be able to lift its tail to defecate and urinate.”

A shorter tail leaves the breech exposed to sunlight, which can lead to cancers of the perineal region. Research conducted in the 1980s found squamous cell carcinomas present in flocks on 82% of farms surveyed. The prevalence of cancers ranged from 0.12% to 4.0% of ewes, and increased with age. More than 3% of ewes over five years of age were affected. Most cancers involved lesions of the vulva and led to the animal being euthanased.

Rectal prolapse is also more common in sheep with short docked tails, due to muscle damage. If sheep are coughing from pneumonia, which is common across all sheep-raising regions of Australia, they are much more likely to suffer rectal prolapse if the tail has been docked too short. Prolapse is generally fatal.

“There are many sound reasons to dock in such a way that an optimal length tail is created,” Dr Lloyd said. “There are no good reasons to dock it shorter than that.”